Visual Nibbling

Great design starts with what you feed your eyes. Amina explores how regular exposure to high-quality visuals, from architecture to nature, rewires your brain, sharpens creative intuition, and builds visual taste that no algorithm can replicate.

nibble /ˈnɪbl/ verb – take small bites out of.

The neurological process behind creating a mediocre design versus an impeccable one has been troubling me for quite some time. If that sounded vague, let me rephrase:What makes a designer create great designs? Looking back at my early days as a teenage design enthusiast, most of what I created now feels pretty mediocre. I observe a similar pattern in junior designers from various design communities today: many possess solid educational backgrounds and technical skills, yet their work often lacks that elusive spark—that subtle, intuitive quality that elevates a design from competent to genuinely compelling. We can list countless practices that help designers grow: reverse-engineering existing great designs, experiencing bad design firsthand, immersing ourselves in the thought processes of more experienced designers, and practice. One crucial thing I did not mention is getting inspired.

Many platforms today assist designers with inspiration. They can be helpful when one needs quick insight, but they may also overwhelm our creative pipelines with ready-made, overused solutions. What I wish to explore is something more subtle, more habitual and what I like to call Visual Nibbling.

Now, let me be clear. I don’t claim to have a formula for a successful growth as a designer nor am I the ultimate judge of what constitutes good or bad design. I’m certainly not a neuroscientist. I’m simply a full-stack designer with a keen amateur interest in cognitive psychology.

What is Visual Nibbling?

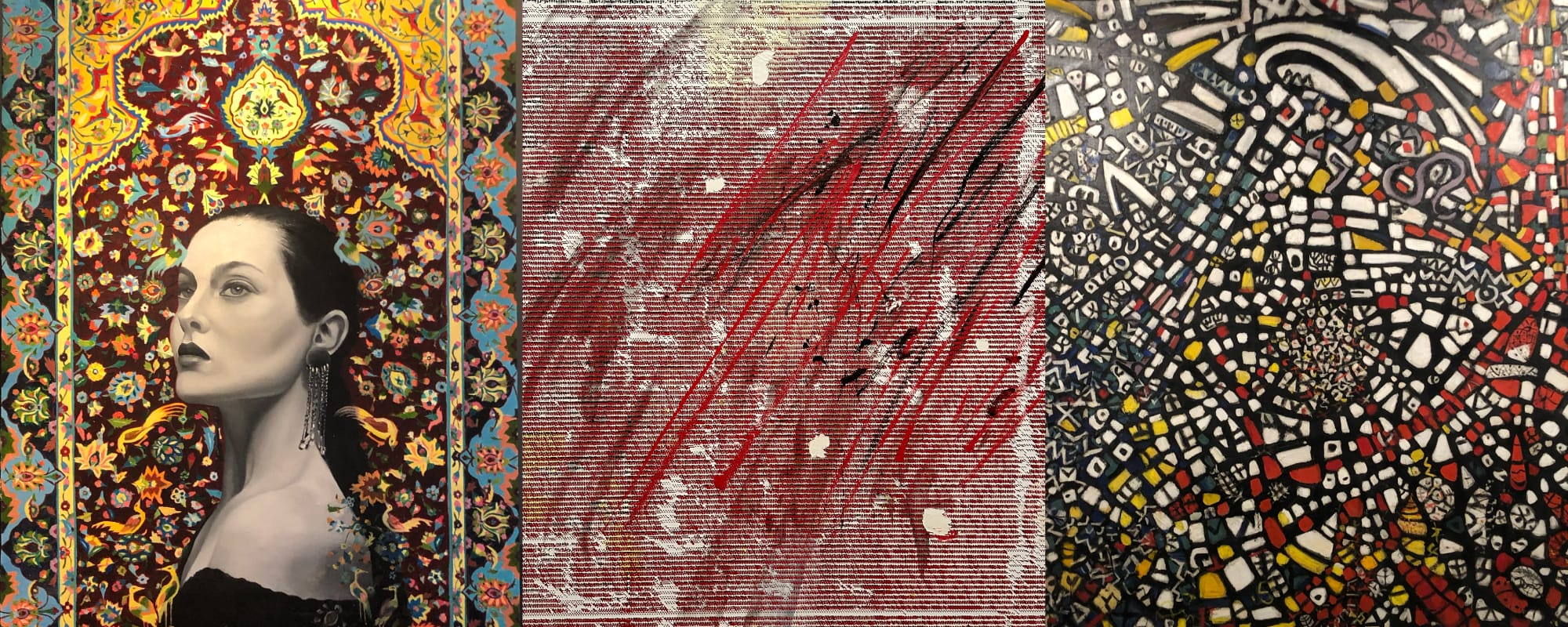

Visual Nibbling is the small, deliberate act of feeding your brain with good visuals that are unrelated to design on a regular basis: art, photography, architecture, nature, even well-composed film scenes. It’s about intentional exposure to high-quality visual stimuli. Think of it as grazing—daily bites of beauty, proportion, balance, chaos, and order. Over time, this diet of excellence begins to rewire how we see, evaluate, and create.

Here’s why that matters: According to Martinez-Conde and Macknik (2012), “more than 50 percent of the cortex, the surface of the brain, is devoted to processing visual information” (p. 2). That’s more than all other senses combined. Vision isn’t just how we see the world, it’s how we think through it. And for designers, it’s the first and most powerful interface between the brain and the work.

Why It Works

When you regularly expose yourself to great visuals—especially those outside your design sphere—your brain begins to build a visual memory bank: patterns, colour harmonies, spatial relationships, and emotional triggers. These stored impressions gradually become the scaffolding for your visual decisions.

This concept becomes even more compelling when viewed through the lens of neuroscience. Tyler and Likova (2012) argue that visual engagement not only activates perceptual systems but also stimulates emotional and cognitive networks. According to the paper, aesthetic experiences (those that provoke reflection, curiosity, and affect) activate brain regions that influence how we feel, remember, and reason. In essence, looking at great visuals doesn’t just make you see better, it helps you think better.

This reminds me of something one of my architectural design lecturers, Dr. Saitali Köknar, used to say:

“Seeing is copying.”

At the time, I found the phrase a bit odd, but I never challenged it. Now, after years of graduating and moving across various branches of design, I fully understand what he meant. Seeing is storing. It is the act of internalising a design solution and, later, retrieving it from memory when it's most needed. It’s not stealing. It’s the application of a learned visual composition or structural solution in a new context, adapted through your own intuition and taste.

This is cognitive priming at work: the brain uses past exposure to make faster, more intuitive decisions. Over time, this shapes what we often refer to as “taste” or “eye.” You start to recognise what works before you can even articulate why it works. That’s because your visual system is operating on more refined, interconnected pathways.

Visual Nibbling also enhances pattern recognition, which is fundamental in design. With regular exposure to well-crafted visuals, you begin to pick up on recurring structures, relationships in proportions, the harmony or tension between colours, the weight of visual elements, and the subtleties of spatial arrangements. It’s like training a muscle: over time, your visual intuition becomes sharper and more responsive. You start recognising when a layout feels off, not because you’ve analysed it line by line, but because something within you instinctively senses the imbalance. It’s the kind of knowledge that lives in the hands and the eyes before it ever reaches the brain.

This cultivated sensitivity also means you're quicker to respond to unfamiliar design problems. Whether you're handed an oddly-shaped component, a cluttered dashboard, or a new branding palette that doesn't quite sing, your brain starts drawing from that internal library of visual experiences. You've already seen balance in asymmetry, harmony in contrast, and elegance in restraint, so you can now recreate them even under pressure.

The only downside? Unfortunately, it develops a rather expensive taste. Your eye begins to crave crafted perfection like it’s haute couture. Suddenly, anything mass-produced feels like a personal insult. Your favourite fonts start costing real money. You find yourself admiring kerning on boutique chocolate packaging or the spacing on a museum label. Visual nibbling refines your judgment, but it also ruins you for mediocre.

Curious how small, intentional design insights can fuel your product vision?

Becoming a Better Designer - One Bite at a Time

Visual Nibbling isn’t a shortcut to good design. It won’t replace practice, critique, iteration, testing or years of honing your craft. But it builds the underlying wiring that great design depends upon. So nibble daily. Keep your eyes well-fed. Observe the balance of elements in an Art Deco building façade. Pause to take in the colour palette in a film still. Let the golden ratio of a flower subtly inform your next composition.

Your brain is hungry. And whether you realise it or not, it’s shaping you into a better designer—one tiny bite at a time.

References

Martinez-Conde, S., & Macknik, S. L. (2012). The science of art. University of Rochester Review, 74(4). Retrieved from https://www.rochester.edu/pr/Review/V74N4/0402_brainscience.html

Tyler, C. W., & Likova, L. T. (2012). The role of the visual arts in enhancing the learning process. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00331